In this article Kun He talks about Chinese-style populism. This is an interesting and important article not only because it focuses on a rather neglected case when it comes ot populism (populism in non-democratic settings is a unicorn in this field), but also because it makes it possible expand our understanding of populism to include a non-Western perspective. What happens to populism when we stop thinking about it in the context of democratic countries? Well, in the Chinese case, first we have to distinguish between communist populism and online bottom-up populism. Then, we must consider that both types of populism, combined, act as a pressure valve for the social volcano that is China.

The Blank Paper Protests are over, but online populism remains alive.

Enjoy the read.

Both populism and communism are often regarded as a threat or challenge to democracy. While communism has waned, populism follows like a shadow (Canovan, 1999). There has been a proliferation of scholarly work on populism in democratic contexts such as Europe, Latin and North America, but the manifestation of populism in a country with a communist background, such as China, remains largely unknown to both the public and to scholars outside of China.

Does populism even exist in China? Some argue that it doesn’t, but according to the Journal of People’s Forum, an academic journal affiliated with the People’s Daily, China has witnessed a rise in populism: it was the most significant ideological trend in China during 2016 and 2017, and remained among the top three most powerful ideologies from 2018 to 2020. Based on a meta-analysis on Chinese populism (Chen, 2011), we know that Chinese populism has distinct socio-cultural features when compared to populism in democracies (Chou, Moffitt & Bryant, 2019; He, Eldridge & Broersma, 2021). This short article shows how we can expand our understanding of populism to include an Eastern perspective, widening from democratic contexts to a party-state with a communist background, and from offline to online populism, by examining the unique nature of populism and how it manifests in China.

The coexistence of communist populism and online bottom-up populism

A distinctive feature of Chinese populism is the coexistence of communist populism and online bottom-up populism. Communist populism invokes the wisdom, identity, value, and revolutionary potential of “the people” and protests against the perceived “corrupt elite”. This concept is deeply ingrained in China’s communist society and culture. For instance, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) legitimizes its governance by appealing to and governing in the name of the majority of people. This is embedded in the government’s communist discourse, such as “the mass” in the Mass Line discourse (1920s-1970s), and references to the “overwhelming majority of the people” in the Three Represents discourse (1990s-2000s) and “the Chinese nation” in the Rejuvenation discourse (2010s-now). Furthermore, the antagonism between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie found in communism is echoed in a populist antagonism between “the people” and “the elite”. Both communism and populism establish this antagonism by developing opposition between a “pure” majority and an “evil” corrupt group, whether this is in opposition to the bourgeoisie in communism or the elite in populism (He, Eldridge & Broersma, 2021).

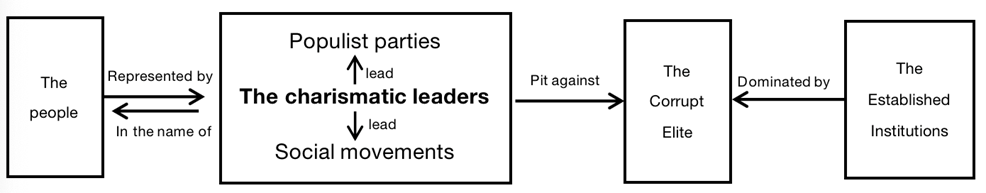

Parallel to communist populism, online bottom-up populism in China manifests differently from populist in democratic contexts. In democratic contexts, populism is often top-down, with charismatic leaders at the top functioning as mediators of populism, positioning themselves as acting in the name of “the people”.

Figure 1 – Top-down populism in Euro-American contexts

Populism in China is distinguished by its online and bottom-up nature. In online bottom-up populism, the people, covered by the semi-anonymous features of the internet, join together as an active community of netizens to raise their voices, and express concerns and even discontent directly and connectively online. By reflecting on online bottom-up populism in China, we can develop new ways of understanding populism globally. It also introduces new questions. For example, to what extent do netizens represent “the people” when they engage in populist discourse? And to what extent does their expression of public opinion represent the general will of “the people”?

Figure 2 – Online bottom-up populism in China

Populism as a pressure valve for the Chinese social volcano

Despite the emergence of a uniquely online, bottom-up form of populism in China, the Chinese state apparatus, political structure, and society remain relatively stable. This is also distinct from other examples of the emergence of populism in democratic contexts. The underlining reasons can be partly attributed to the coexistence of communist populism and online bottom-up populism. These two sub-forms of populism are competing, cooperating, and gaming with each other. As a result, they combine to serve as a “pressure valve” for the Chinese “social volcano.” This novel understanding of populism moves our impression of populism from “pathological symptoms”, threats or challenges to democracy, to a control of public discontent, allowing the state to permit or generate populist discourses as a way to release social unrest, doing so in a controlled and stabilizing manner.

First, in terms of competition, communist populism dampens the discursive power of online bottom-up populism, particularly when it targets established institutions that are led by the communist party. In these instances, a communist populist discourse that values and respects the ideas, concerns, and wisdom of “the people” is invoked. This is referenced in the Mass Line discourse credited to Mao Zedong (1920s to 1970s) and its slogan “To the masses – from the masses – to the masses”. Within a populist frame, this is interpreted as a process of first investigating people’s conditions, learning about and engaging in their struggles, gathering ideas from them, and then developing an action plan based on these ideas and concerns of the people.

Similarly, in the Three Represents discourse credited to Jiang Zemin (1990s to 2000s) and the Rejuvenation discourse credited to Xi Jinping (2010s-current), attempts to include as many people as possible are made. By claiming to govern in the name of the overwhelming majority of the proletariat and in the name of the Chinese nation, communist populism not only legitimizes and consolidates the authority of the CCP, but also “holds a monopoly on political power that precludes any meaningful opposition or contestation from other political parties or organizations” (Joseph, 2019, p.14). Furthermore, communist rhetoric limits the possibility for online bottom-up populists to make inroads in their appeals in the name of “the people.” This functions as a valve, to release the internal pressure of the Chinese “social volcano” when populist discontent swells online.

Second, the pressure that grows in the “social volcano” can be released by the gaming that goes on between communist and online bottom-up populism. This can be seen in the self-empowerment that social media affords (Shi & Yang, 2016), which allows “the people”, covered by the semi-anonymous nature of the internet, to express their voices and discontent to a certain degree. However, this expression could give rise to online bottom-up populism that could further lead to a societal cleavage between the rich and the poor, the privileged and the underprivileged, and the powerful and the powerless. Meanwhile, the affordances of technologies also allow the government to implement a strict censorship mechanism, aiming to “purify the cultural environment on the internet” (Xinhua News, 2009) by censoring, deleting, and harmonizing content that may potentially polarize society. This censorship takes effect not only through a top-down political but also a bottom-up cultural mechanism.

The top-down political aspect of censorship takes shape through arresting activists who are perceived as threats when organizing offline or online activities, or when spreading disinformation that could exacerbate social gaps. The bottom-up cultural aspect of censorship seeks to engender a culture of self-regulation and self-discipline through social and cultural education movement, forming an awareness of “bounds” (Schroeder, 2021, p.183). Overall, online bottom-up populist articulation together with the operation of censorship function as a “pressure valve” for the Chinese “social volcano,” enabling pressure (voices, concerns, and discontent) to be released in a controlled way. This new perspective makes an effort to explain China’s resistance to populism by demonstrating how a more subtle and indirect type of control is possible within the conflict between censorship and resistance.

Another way communist populism aligns with online bottom-up populism is when both are engaged in redirecting public discontent away from internal issues of inequality and towards external targets who are perceived as enemies of the Chinese nation. We see this when online populist protests focus on corrupt elites perceived as betraying their Chinese identity, or foreign entities perceived as humiliating the Chinese nation. Communist populist discourse often frames these campaigns in a nationalist context, praising those who participate as patriotic defenders of the Chinese nation. For instance, China’s official media, People’s Daily (2016), praised netizens who organized online protests against pro-independent elites in Taiwan, as “good sons and daughters of the Chinese nation, who contribute to the Chinese dream of promoting the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” Similarly, in 2019, the official Weibo account of Central Committee of the Communist Youth League posted “Tonight, belongs to #DibaNetizens#. Patriotic youth online expedition”, mobilizing netizens to protest against Hongkongers perceived to be betraying their Chinese identity. This recontextualizes criticism with a populist stance towards the state, reframing it as a nationalist protest against foreign others or those who betray their Chinese identity. By recontextualizing, the internal populist pressure of “social volcano” (Whyte, 2020) is mitigated and assuaged by the nationalist’s antagonism between the Chinese nation and others.

Kun He is a PhD candidate based on The Centre for Media and Journalism Studies, University of Groningen. His research mainly focuses on Chinese populism, exploring how populism is manifested in a communist setting. He will defend his PhD thesis “Bottom-up and online populism in contemporary China: An understanding beyond the West” at the University of Groningen on June 29, 2023. He currently works as a postdoc, focusing on human AI, digital technology, and politics.